I have a complicated relationship with creativity. I’ve always admired creators and aspired to flex my own creative muscles, but our culture tends to equate creativity with art. Even when I started my career at a creative ad agency in San Francisco, I felt like an interloper. Defined roles labeled others as the “creatives,” while my business degree and client management focus marked me as the “suit.” It was a distinction that I chafed at, but deep down I was also aware that I wasn’t drawn to graphic design or copywriting the way my colleagues were. Over time I found myself gravitating to projects where I could work with brand strategists and digital producers, not realizing that I was taking the first steps towards a career in product management. And completely unaware that my professional journey through product and startups would give me an entirely new perspective on the definition of creativity.

In product management, my job is to help build apps and software that you love. It’s a relatively new discipline (compared to, say, law), but one that thrives on frameworks and techniques designed to uncover the next great product. As Andy Rachleff puts it:

Serendipity plays a role in finding product/market fit, but the process to get to serendipity is incredibly consistent.[1]

The process that Rachleff is talking about here is structured creativity — the system by which you enable the development of new ideas. In many ways, my job is entirely about facilitating (and driving) a team-based creative process. Structured creativity is the backbone of product development, and increasingly an essential skill across all fields. And time and time again, the most useful framework I have found for this skill is the Double Diamond.

Introducing the Double Diamond

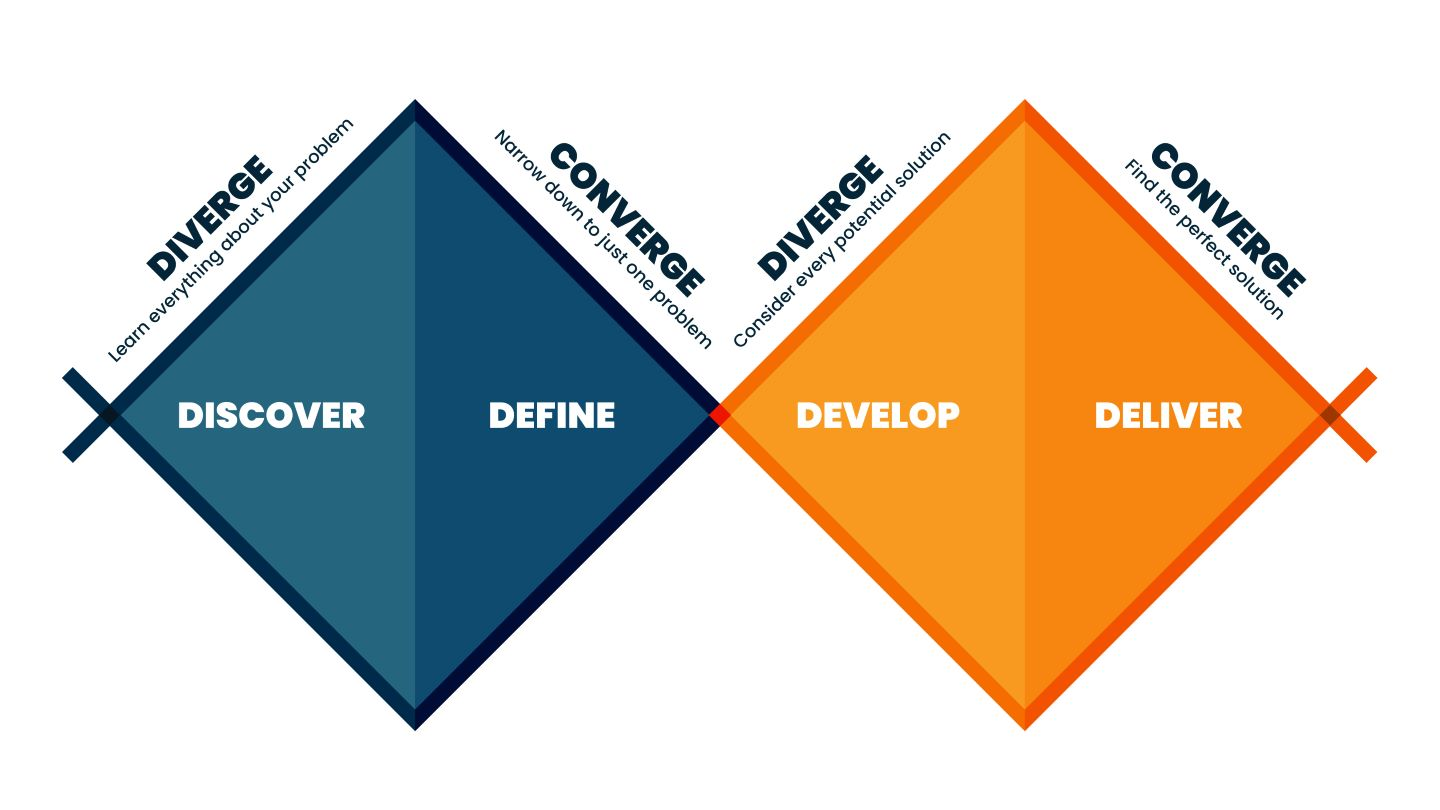

The Double Diamond is a simple yet powerful framework for problem-solving[2]. It’s divided into two main stages or diamonds: Discover-Define and Develop-Deliver, each containing phases of divergent and convergent thinking. The first diamond is all about understanding the problem space — you divergently "Discover" insights through research, then converge to "Define" the core opportunity. The second diamond tackles creating a solution for the defined problem — first diverging to "Develop" a wide range of potential concepts through ideation and prototyping, before converging in "Deliver" through refining, testing, and implementing the strongest solutions. Its elegance and simplicity have long made it a favorite among product managers (PMs), but in my opinion it has much more diverse applications thanks to its two superpowers: its ability to separate core thinking modes and its flexibility.

Superpower 1: Separation

The Double Diamond’s separation superpower first manifests in the existence of two diamonds — the problem and solution stages. The separation pushes you to deeply understand and define the problem (or the “problem space”) before you even start thinking about solutions. This approach fosters clarity of thinking, enabling you to ultimately reason about solutions from first principles. Despite his questionable ethics, Jeff Bezos underlines this concept with his quote about focusing on what won’t change when building a business. He’s making a point about investing in stability, but he’s also revealing how deeply he understands the problems his customers face:

In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that's going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

The clarity of those needs puts his team in a much better position to reason about solutions, as they can evaluate all of their future ideas against how well they solve those core problems and ultimately develop stronger products.

Enforcing this separation is one of the most important facets of a healthy product development process. Tactically, I often do this by explicitly separating the time devoted to each diamond — scheduling separate blocks for problem thinking vs solution thinking, so that you’re more engaged with each. For larger initiatives it can be beneficial to spend multiple weeks purely in problem definition, to ensure that you deeply understand the core needs. Building this separation into your artifacts also helps reinforce the concept — all of my product briefs have a section explicitly devoted to the problem, and I build in gates so that the team is fully aligned on the problem before we move into solution development. Within discussions, it’s also important to look for cues that you’re straying into the solution space. One of the most common (and slippery) expressions of this is the “they just need the thing” statement — if they just had a button that did X, or a simple download that did Y, the user’s life would be complete. The most effective way to disarm this is to simply ask why (and often multiple times) — what does that accomplish for them? Another is to ask your teammate if they think they’re in the problem space or the solution space. While this latter technique requires healthy team dynamics (and buy-in to the separation), naming the mixing can enable everyone in the room to zoom back out to the problem.

The second manifestation of this superpower is the delineation of divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking, which is the left-hand phase of both diamonds, involves exploring a wide range of possibilities and generating numerous ideas without immediate judgment. It’s about expanding horizons, considering various perspectives, and fostering creativity and innovation. Conversely, convergent thinking, or the right side of the diamonds, focuses on narrowing down these ideas, evaluating them critically, and selecting the most viable solutions. It’s about refining, organizing, and implementing ideas in a structured manner. The benefits of this separation are rooted in psychology — Daniel Kahneman, in his seminal Thinking Fast and Slow, outlined that our brain uses two systems to process information. System 1 is the fast, intuitive method associated with divergent thinking, while System 2 is the slow, logical thinking used for convergence. Separating the two processes enables you fully engage with each system and leverage its strengths, but using the two of them in the same structured process unlocks higher quality outputs.

In practice, separating divergent and convergent thinking also benefits from dedicated time blocks, although I find that they can be closer together. I often have both processes in the same session, with the first portion devoted to divergence and the second reserved for convergence. This is in contrast to separating problem and solution thinking, where you often benefit from having time between to fully process the problem. In the moment, the biggest pitfall tends to be during divergent thinking — for a lot of people, it can be hard to generate ideas because they’re editing them before they’re even out on paper. I find that there are two useful techniques for counteracting this. The first is recognizing that creativity, in some ways, is a numbers game — you need to generate a lot of bad ideas in order to find the good ones. The second is, counterintuitively, shortening the time you give yourself for divergence — the pressure forces System 1 to kick into gear and rapidly generate ideas.

Superpower 2: Flexibility

Beyond its ability to separate thinking modes, the Double Diamond’s flexibility superpower is what makes it the backbone of my product processes. It can flex up and down in time — for a large initiative, you may spend a month in problem definition and then multiple months developing solutions to that core problem. You can also work the process over the course of a few days — this approach is effectively the design sprint laid out by Google alums in Sprint. It’s also important to note that there’s a natural decision point at the end of both diamonds — you don’t need to build a solution to every problem and you don’t need to release every solution that you build. Indeed, early stage companies will often go through the problem diamond multiple times before even beginning to think about solutions — at that stage, you’re trying to find a problem that’s worth solving (i.e. one that can support a business) and may need to go through multiple rounds of problem definition before they find that opportunity. Similarly, teams may work through the solution diamond multiple times in succession, iterating towards a product that solves a larger problem.

The Double Diamond as a Creative Foundation

Taken together, these two capabilities make the Double Diamond my foundational approach to developing ideas, even beyond product development. I believe it’s a metaframework for creativity and problem solving that can be used across disciplines and can integrate with a variety of approaches. It’s also why I like to reframe the problem diamond as the “opportunity stage” — it’s not just about identifying a problem, but more generally recognizing an idea that can be developed. One of my favorite examples of this in practice is from musician Will Wiesenfeld:

In my process I only really take a song to its full ending if I have something in my head which I like to call the bones of a song… Like with “Do I Make the World Worse,” there was just this rhythm that’s been the bones of the song the whole time. I knew that was always the thing that was important, and I was gonna work on finding what that wanted to give me. That was the part that was important, but there could have been like six or seven different outcomes to that one idea. That’s also an exercise I’ve done in the past, taking one skeletal structure for a song, taking five different attempts at it, and using the best version.[3]

Here the bones of the song is the opportunity — this is the idea that Wiesenfeld converged on from all of his divergent influences. And he often will divergently experiment with multiple variations of a song structure before converging on the final, released track. The same principle can even apply to something as mundane as balancing your accounting books. Say you have a discrepancy in your final numbers. You start by identifying the problem — divergently exploring your different reports and transactions before identifying the source of the discrepancy. Next you figure out the solution — listing out the possible ways you could resolve the issue before weighing their pros and cons and implementing your choice. Two processes, worlds apart, both anchored by a structured creative approach.

We’re at the beginning of an era that is likely to highly value creativity. The 2023 Future of Jobs report from the World Economic Forum predicted that almost half (44%) of workers’s core skills will be disrupted by 2027, and that the most important skills as we navigate this change are analytical and creative thinking. These skills are going to be the foundation for the Future of Work, and the Double Diamond is a powerful metaframework for developing your own structured creativity.

Footnotes

developed in 2005 by the British Design Council

Enjoyed this post? Get more like it in your inbox.